Each "chapter" of the book has a different title, taken from some well-known songs and some more obscure ones - I assume chapter 14 is like the rest of the titles and is taken from the song Working Girls and Brides, but it is omitted from this mix because I can't find any evidence that it exists.

These song titles, uncredited to any original artist in the context of the book, only hint at what their accompaniment might be, and it is only the memory of the more well-known songs that may provide any context unless you were to listen to each song as you looked through the book.

[The full "track list" is only available in the book, to my knowledge. I could not find it online and the one Spotify playlist of the songs from the book that does exist is incomplete.]

The book is known for its grit, its realism, its honesty, but would this still be the case if each chapter were considered alongside its namesake? I wonder.

I am interested in bringing image and music together not as accompaniment, but considering the worth of both photo sequence and mix tape equally, on a level playing field, as well as the unique experience that the combination of the two creates.

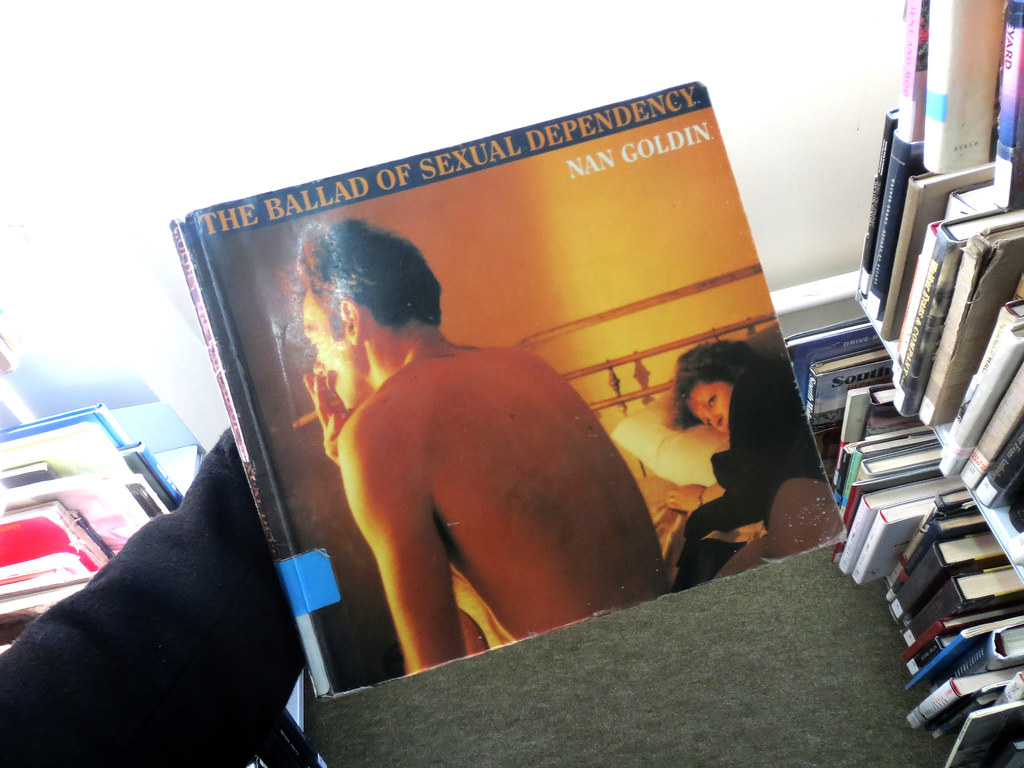

The Ballad is the perfect example of where this unique experience has been lost, discarded for the preferred experience of sitting alone in a room with the book on your knee. Some of the songs presented here would not be my choices, but that is what makes them interesting. I think Nan Goldin's photographs are good - for want of a better, but relatively neutral word - but Lonely Boy by Andrew Gold, as a song, for example, is sickly sweet, as are some of the other songs here, and that makes their placement alongside Goldin's photographs laughable, and then, quickly, quite sinister. Do such light-hearted songs belong next to such heavily-weighted images? Does Goldin want us to consider the images as the former rather than the latter?

Lonely Boy is also, in my opinion, a horrendous song. Should this colour the section of the work I'm looking at? Should I disregard one in favour of the other because they are different mediums? - that's too easy - Or should I consider them both together, jarringly, and have an altogether new experience from this collision?

Some of the songs here fit nicely with the world Goldin presents us with - the Louisiana Red track being even more horrifying in Goldin's context than it is in its own right and The Intruders, a soul group I am personally very fond of, have been tainted forever with their lyrics presented in a new, and ultimately misogynistic, light - others couldn't possibly be more at odds with the images we are looking at, at least in terms of sound ... I'm looking at you again, Andrew Gold.

I have read reports that these choreographed slideshows lasted for 45 minutes although there is no record of the songs played in that environment. This mix is an hour long and some of the tracks have been shortened in line with my own aesthetic judgement. Some tracks also have multiple versions by different artists, so my own judgement can be seen again there. Therefore this mix is by no means faithful to The Ballad's original context. It is also unfaithful to its original photobook context. In my opinion, this collection of songs is a far more interesting window to look at Goldin's work through, disregarding the tell-all autobiographical introductory text that welcomes in her photobook and overshadows the contents page just before it.

Goldin has cast a long shadow, with photographs of (mostly) young people engaged in controversial and / or sexual activities being hard to ignore in photography even now, and that's not for lack of trying. I'm prepared to engage with Goldin's book again with this mix firmly jammed in between its pages, and it's about time it was generally considered in this way again, beyond its original legend of origin.

No comments:

Post a Comment